The shaping of a research question requires a number of clinical, academic, and practical considerations, said Professor Martin Stout, Consultant Cardiac Physiologist at the North West Heart Centre in Manchester’s Wythenshawe Hospital.

“You need a sound knowledge regarding research processes, and knowledge of your clinical speciality, as well as ethical issues that may be involved in the study itself,” he said.

Choose your question

“The first point to address is what is your research question – what do you want the study to find out?”, he said, adding that, ideally, it would be rooted in clinical and academic experience.

“I usually discover the best research avenues based on areas that I've worked in for a long period, as I can understand the many ins, outs, limitations and advantages to specific pathways, diagnostics or treatments. I can then try and address exactly what needs to be done to improve clinical care.”

Build your team

Researchers should interact with colleagues from different backgrounds to create a collaboration between medics, scientists, and academics, said Prof Stout.

“I would consider approaching statisticians, ethical teams, educators, clinical academics, lead clinicians – all these people might be able to play a key role in the research process.”

A supportive environment is essential, he went on, explaining that it was “extremely problematic” to attempt research in a department that requires 24/7 testing, for example.

Conduct a literature review

Before embarking on a study, researchers need to ensure their work will be worth the investments of time, money, and resources – particularly if the project is grant funded or part of a fellowship.

A thorough literature review provides “an excellent basis” for this, said Prof Stout. Ideally, the review will highlight the lack of evidence in the chosen area, or conflicting results or poor methodology across multiple studies, meaning that better study design or higher study power could contribute to the evidence base.

“Following these steps, narrow down your research question, and remove unnecessary components that might affect your generalizability,” said Prof Stout. “Define a clear target population, a specific intervention, an alternative treatment or diagnostic assessment, a primary outcome that is robust, measurable, and repeatable, and a realistic timeframe by using the combined knowledge from the literature search, your experience, and the wider research team.”

Sometimes, he said, researchers need to reshape the question to best match what it is feasible to achieve with the resources available.

Frameworks

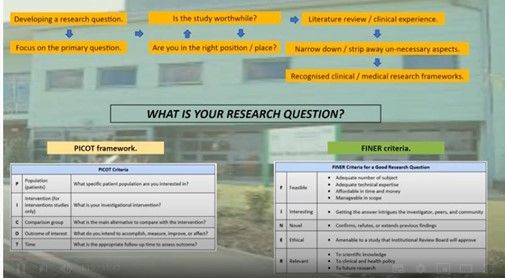

Prof Stout pointed to two useful frameworks that can help researchers navigate the process of setting up a study: PICOT and FINER (see fig 1).

|

| Figure 1: Shaping your research question |

“Both have overlap, but one may be more useful than the other, dependent on the situation you find yourself in as a researcher, or the type of research question you wish to ask,” he said.

“The PICOT framework is designed to allow the researcher to formulate a good research question and to facilitate an effective literature search. The FINER criteria help further refine, by factoring in the practical aspects of time and resources.”

Ethical considerations are also important, he said, advising delegates to utilise research and development teams within their local trust to ensure compliance with research good clinical practice. “Ethical processes will likely be considered by external panels, who will scrutinise the study design in respect of practicality, novelty, safety, interest, and feasibility. It's good practice to ensure these components are clearly assessed prior to any ethical panel submission.”

Interesting and novel

Research projects should bridge a gap in current knowledge and have the potential to change the treatment or diagnostic pathway of a patient group.

“Usually, high-impact factor journals only accept studies of this nature. But lower impact journals may be willing to accept less novel studies if there is an inherent interest to clinical practice.

“Ultimately, the final outcome is publication. Therefore, the novelty and interest of your work must be considered and aligned to the desired final output,” concluded Prof Stout.

BSEcho 2020 presentations are available on our website for members of the Society.

View the presentations